Difference between revisions of "Creating an Android User Interface in Java Code"

m (Text replacement - "<table border="0" cellspacing="0" width="100%">" to "<table border="0" cellspacing="0">") |

m (Text replacement - "<hr> <table border="0" cellspacing="0"> <tr>" to "<!-- Ezoic - BottomOfPage - bottom_of_page --> <div id="ezoic-pub-ad-placeholder-114"></div> <!-- End Ezoic - BottomOfPage - bottom_of_page --> <hr> <table border="0" cellspacing="0"> <tr>") |

||

| Line 385: | Line 385: | ||

| + | <!-- Ezoic - BottomOfPage - bottom_of_page --> | ||

| + | <div id="ezoic-pub-ad-placeholder-114"></div> | ||

| + | <!-- End Ezoic - BottomOfPage - bottom_of_page --> | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

<table border="0" cellspacing="0"> | <table border="0" cellspacing="0"> | ||

Revision as of 19:37, 10 May 2016

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

| Designing an Android User Interface using the Graphical Layout Tool | Using the Android GridLayout Manager in the Graphical Layout Tool |

An alternative to writing XML resource files or using the Graphical Layout tool is to write Java code to directly create, configure and manipulate the view objects that comprise the user interface of an Android activity. Within the context of this chapter, we will explore some of the advantages and disadvantages of creating a user interface layout in Java code before describing some of the key concepts such as view properties, layout parameters and rules. Finally, an example project will be created and used to demonstrate some of the typical steps involved in this approach to Android user interface creation.

Contents | ||

Java Code vs. XML Layout Files

There are a number of key advantages to using XML resource files to design a user interface as opposed to writing Java code. In fact, Google goes to considerable lengths in the Android documentation to extol the virtues of XML resources over Java code. As discussed in the previous chapter, one key advantage to the XML approach includes the ability to use the Graphical Layout tool, which, itself, generates XML resources. A second advantage is that once an application has been created, changes to user interface screens can be made by simply modifying the XML file, thereby avoiding the necessity to recompile the application. Also, even when hand writing XML layouts, it is possible to get instant feedback on the appearance of the user interface by switching back and forth between the XML editor and the Graphical Layout tool within the Eclipse environment. In order to test the appearance of a Java created user interface the developer will, inevitably, repeatedly cycle through a loop of writing code, compiling and testing in order to complete the design work.

In terms of the strengths of the Java coding approach to layout creation, perhaps the most significant advantage that Java has over resource files comes into play when dealing with dynamic user interfaces. XML resource files are inherently most useful when defining static layouts, in other words layouts that are unlikely to change significantly from one invocation of an activity to the next. Java code, on the other hand, is ideal for creating user interfaces dynamically at run-time. This is particularly useful in situations where the user interface may appear differently each time the activity executes subject to external factors.

Finally, some developers simply prefer to write Java code than to use layout tools and XML, regardless of the advantages offered by the latter approaches.

Creating Views

As previously established, the Android SDK includes a toolbox of view classes designed to meet most of the basic user interface design needs. The creation of a view in Java is simply a matter of creating instances of these classes, passing through as an argument a reference to the activity with which that view is to be associated.

The first view (typically a container view to which additional child views can be added) is displayed to the user via a call to the setContentView() method of the activity. Additional views may be added to the root view via calls to the object’s addView() method.

When working with Java code to manipulate views contained in XML layout resource files, it is necessary to obtain the ID of the view. The same rule holds true for views created in Java. As such, it is necessary to assign an ID to any view for which certain types of access will be required in subsequent Java code. This is achieved via a call to the setId() method of the view object in question. In later code, the ID for a view may be obtained via a subsequent call to the object’s getId() method.

Properties and Layout Parameters

Whilst property settings are internal to view objects and dictate how a view appears and behaves, Layout Parameters are used to control how a view appears relative to its parent view and other sibling views. Layout parameters are not set in quite the same way as properties, but rather stored in a ViewGroup.LayoutParams instance (or a subclass thereof) which is then either passed through as an argument when the view is added to the parent view, or assigned to the child view via a call to the view’s setLayoutParams() method.

A LayoutParams object for a view is typically created by declaring how the view should be sized in relation to the parent view (i.e. whether it should fill the parent or be sized to fit the content it needs to display). Once the LayoutParams object exists, additional rules, such as whether the view should be aligned with another view, can be added via calls to the addRule() method of the LayoutParams object.

There are subclasses of ViewGroup.LayoutParams for each of the layout types (AbsoluteLayout.LayoutParams, RelativeLayout.LayoutParams and so on).

Having covered the theory of user interface creation from within Java code, the remainder of this chapter will work methodically through the creation of an example application with the objective of putting this theory into practice.

Creating the Example Project

Launch Eclipse and create an Android Application Project named JavaLayout with the appropriate package name and SDK selections. As with previous examples, request the creation of a blank activity and the use of the default launcher icons. Name the activity JavaLayoutActivity and the corresponding layout activity_java_layout with the fragment layout named fragment_java_layout.

Once the project has been created, navigate within the Package Explorer panel to src -> <package name> and double click on the JavaLayoutActivity.java file so that it loads into an editing panel. As we have come to expect, Eclipse has created the template activity and overridden the onCreate() method, providing an ideal location for Java code to be added to create a user interface.

Adding Views to an Activity

The onCreate() method is currently designed to use a resource layout file and a fragment for the user interface. Begin, therefore, by deleting these lines from the method so that it reads as follows:

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

}

The next modification to the onCreate() method is to write some Java code to add a RelativeLayout object with a single Button view child to the activity. This involves the creation of new instances of the RelativeLayout and Button classes. The Button view then needs to be added as a child to the RelativeLayout view which, in turn, is displayed via a call to the setContentView() method of the activity instance:

package com.example.javalayout;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.ActionBar;

import android.app.Fragment;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.LayoutInflater;

import android.view.Menu;

import android.view.MenuItem;

import android.view.View;

import android.view.ViewGroup;

import android.os.Build;

import android.widget.Button;

import android.widget.RelativeLayout;

public class MainActivity extends Activity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

Button myButton = new Button(this);

RelativeLayout myLayout = new RelativeLayout(this);

myLayout.addView(myButton);

setContentView(myLayout);

}

.

.

.

}

Once the above additions have been made, compile and run the application (either on a physical device or an emulator). Once launched, the visible result will be a button containing no text appearing in the top left hand corner of the RelativeLayout view.

Setting View Properties

For the purposes of this exercise, we need the background of the RelativeLayout view to be blue and the Button view to display text that reads “Press me”. Both of these tasks can be achieved by setting properties on the views as outlined in the following code fragment:

package com.example.javalayout;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.ActionBar;

import android.app.Fragment;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.LayoutInflater;

import android.view.Menu;

import android.view.MenuItem;

import android.view.View;

import android.view.ViewGroup;

import android.os.Build;

import android.widget.Button;

import android.widget.RelativeLayout;

import android.graphics.Color;

public class MainActivity extends Activity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

Button myButton = new Button(this);

myButton.setText("Press me");

myButton.setBackgroundColor(Color.YELLOW);

RelativeLayout myLayout = new RelativeLayout(this);

myLayout.setBackgroundColor(Color.BLUE);

myLayout.addView(myButton);

setContentView(myLayout);

}

.

.

.

}

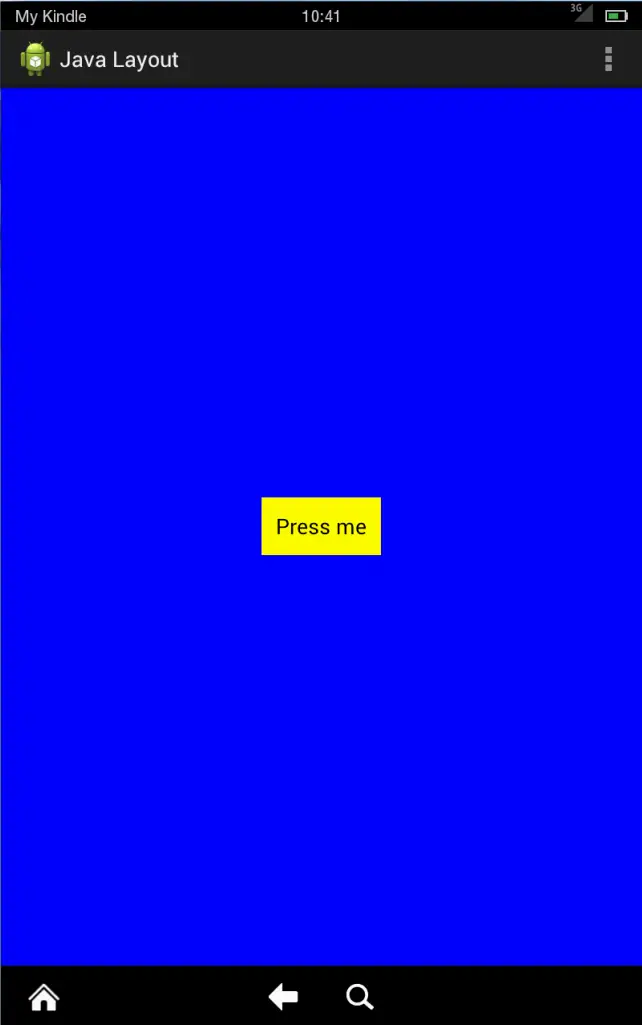

When the application is now compiled and run, the layout will reflect the property settings such that the layout will appear with a blue background and the button will display the assigned text on a yellow background.

Adding Layout Parameters and Rules

By default, the RelativeLayout view has placed the button view in the top left corner of the display. In order to instruct the layout view to place the button in a different location, in this case centered both horizontally and vertically, it will be necessary to create a LayoutParams object and initialize it with the appropriate values.

Typically, a new LayoutParams instance is created by passing through the height and width values for the view. These values should be set to either MATCH_PARENT, WRAP_CONTENT or specific size values. The MATCH_PARENT setting instructs the parent layout to expand the child view so that it matches the size of the parent. WRAP_CONTENT, on the other hand, instructs the parent to size the child view so that it is only large enough to display any content it may be configured to show to the user.

The code to create a LayoutParams object for our button would read as follows:

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams buttonParams =

new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

The above code creates a new RelativeLayout LayoutParams object named buttonParams and sets the height and width such that the button will only be large enough to display the “Press Me” text previously configured via the property setting.

Now that the LayoutParams object has been created, the next step is to add some additional rules to the parameters to instruct the layout parent to center the button vertically and horizontally. This is achieved by calling the addRule() method of the buttonParams object, passing through the appropriate values as arguments:

buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_HORIZONTAL); buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_VERTICAL);

Simply creating a new LayoutParams object and configuring it is only useful if that object is then assigned to the child view. One way to achieve this is to pass the LayoutParams object through as an argument when the child view is added to the parent:

myLayout.addView(myButton, buttonParams);

Alternatively, the parameters can be assigned to the child via a call to the setLayoutParams() method of the view:

myButton.setLayoutParams(buttonParams);

Bringing these together results in a modified onCreate() method that reads as follows:

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

Button myButton = new Button(this);

myButton.setText("Press me");

myButton.setBackgroundColor(Color.YELLOW);

RelativeLayout myLayout = new RelativeLayout(this);

myLayout.setBackgroundColor(Color.BLUE);

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams buttonParams =

new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_HORIZONTAL);

buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_VERTICAL);

myLayout.addView(myButton, buttonParams);

setContentView(myLayout);

}

Having made the above changes, compile and run the application once again, this time noting that the button is now centered within the RelativeLayout view as illustrated in Figure 14-1:

Figure 14-1

In order to gain a clearer understanding of the height and width layout parameter settings, temporarily modify the buttonParams creation code to read as follows, then re-compile and run the application:

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams buttonParams =

new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.MATCH_PARENT,

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.MATCH_PARENT);

With both the height and width parameters set to MATCH_PARENT, the button is now sized to match the parent view and consequently fills the entire display.

Before continuing, revert the height and width settings to WRAP_CONTENT.

Using View IDs

So far in this tutorial it has not been necessary to use view IDs. In order to demonstrate the use of IDs in Java code, the example will now be extended to add another view in the form of an EditText view that will be configured to be aligned 80 pixels above the existing button and centered horizontally. The following code modifications add the new view to the activity and then set IDs of 1 and 2 on the Button and EditText views respectively. Layout parameters are then created for the EditText view so that it is aligned with the button (note the call to getId() on the button to get the view ID) and centered horizontally within the layout. Finally, the margins property of the EditText field is configured to set the bottom margin to 80 pixels before adding the new view to parent layout:

package com.example.javalayout;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.ActionBar;

import android.app.Fragment;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.LayoutInflater;

import android.view.Menu;

import android.view.MenuItem;

import android.view.View;

import android.view.ViewGroup;

import android.os.Build;

import android.widget.Button;

import android.widget.RelativeLayout;

import android.graphics.Color;

import android.widget.EditText;

public class MainActivity extends Activity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

Button myButton = new Button(this);

myButton.setText("Press me");

myButton.setBackgroundColor(Color.YELLOW);

RelativeLayout myLayout = new RelativeLayout(this);

myLayout.setBackgroundColor(Color.BLUE);

EditText myEditText = new EditText(this);

myButton.setId(1);

myEditText.setId(2);

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams buttonParams =

new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams textParams =

new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

textParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.ABOVE, myButton.getId());

textParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_HORIZONTAL);

textParams.setMargins(0, 0, 0, 80);

buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_HORIZONTAL);

buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_VERTICAL);

myLayout.addView(myButton, buttonParams);

myLayout.addView(myEditText, textParams);

setContentView(myLayout);

}

.

.

.

}

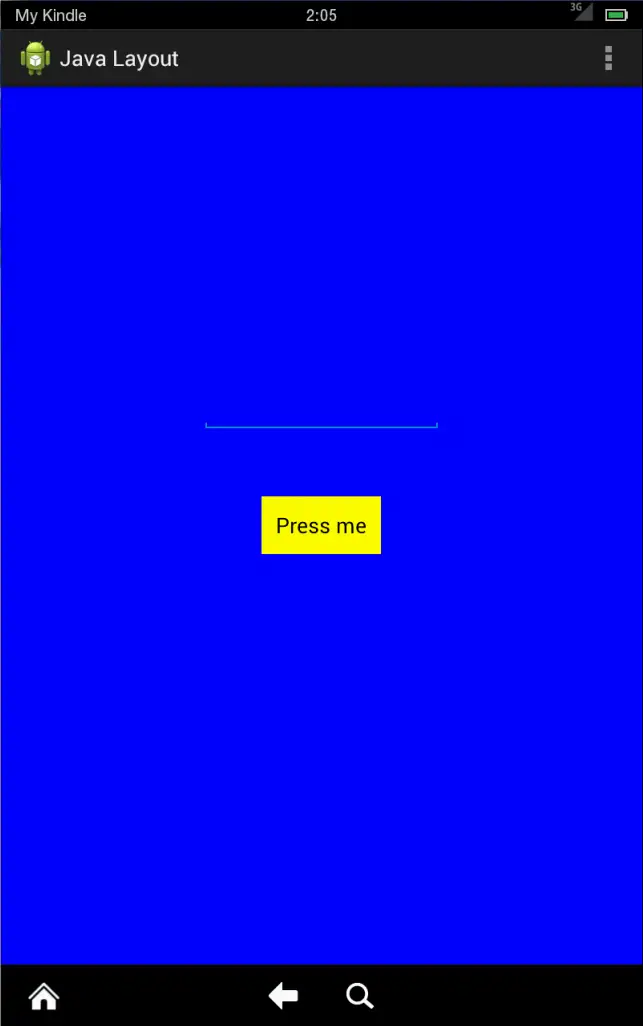

A test run of the application should show the EditText field centered above the button with a margin of 80 pixels.

Converting Density Independent Pixels (dp) to Pixels (px)

The final task in this exercise is to set the width of the EditText view to 200dp. As outlined in the chapter entitled Designing an Android User Interface using the Graphical Layout Tool, when setting sizes and positions in user interface layouts it is better to use density independent pixels (dp) rather than pixels (px). When the margin was set in the above section, the value was declared in px instead of dp. The reason for this was that such method calls only accept values in pixels. In order to set a position using dp, therefore, it is necessary to convert a dp value to a px value at runtime, taking into consideration the density of the device display. In order, therefore, to set the width of the EditText view to 200dp, the following code needs to be added to the onCreate() method:

package com.example.javalayout;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.ActionBar;

import android.app.Fragment;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.LayoutInflater;

import android.view.Menu;

import android.view.MenuItem;

import android.view.View;

import android.view.ViewGroup;

import android.os.Build;

import android.widget.Button;

import android.widget.RelativeLayout;

import android.graphics.Color;

import android.widget.EditText;

import android.content.res.Resources;

import android.util.TypedValue;

public class JavaLayoutActivity extends Activity {

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

Button myButton = new Button(this);

myButton.setText("Press me");

EditText myEditText = new EditText(this);

myButton.setId(1);

myEditText.setId(2);

RelativeLayout myLayout = new RelativeLayout(this);

myLayout.setBackgroundColor(Color.BLUE);

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams buttonParams =

new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_HORIZONTAL);

buttonParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_VERTICAL);

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams textParams =

new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

textParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.ABOVE, myButton.getId());

textParams.addRule(RelativeLayout.CENTER_HORIZONTAL);

textParams.setMargins(0, 0, 0, 80);

Resources r = getResources();

int px = (int) TypedValue.applyDimension(

TypedValue.COMPLEX_UNIT_DIP, 200, r.getDisplayMetrics());

myEditText.setWidth(px);

myLayout.addView(myButton, buttonParams);

myLayout.addView(myEditText, textParams);

setContentView(myLayout);

}

}

Compile and run the application one more time and note that the width of the EditText view has changed as illustrated in Figure 14-2:

Figure 14-02

Summary

As an alternative to writing XML layout resource files or using the Graphical Layout tool, Android user interfaces may also be dynamically created in Java code. Creating layouts in Java code consists of creating instances of view classes and setting properties on those objects to define required appearance and behavior.

How a view is positioned and sized relative to its parent view and any sibling views is defined using layout parameters, which are stored in LayoutParams objects. Once a LayoutParams object has been created and initialized with height and width behavior settings, additional rules may then be added to configure the parameters further. The example activity created in this chapter has, of course, created the same user interface (the change in background color notwithstanding) as that created in the previous chapter using the Graphical Layout tool and XML resources. If nothing else, this chapter should have provided an appreciation of the level to which the Graphical Layout tool and XML resources shield the developer from many of the complexities of creating Android user interface layouts.

There are, however, instances where it makes sense to create a user interface in Java. This approach is most useful, for example, when creating dynamic user interface layouts that will appear differently each time an activity is launched.

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

| Designing an Android User Interface using the Graphical Layout Tool | Using the Android GridLayout Manager in the Graphical Layout Tool |